For Sale: Software, Never Used

The title of this post is a parody on the infamous For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn. It is an example of what is sometimes called, “Flash Fiction.” While the title of this is a parody, it has remained a work of non-fiction in many of the organizations I’ve been in.

What I am going to attempt to do is list some of the top factors for this tragic tale. Maybe there will be something in it for you.

-

Imaginary Customers

Lets be honest, most of the time the idea of a user is a vague abstraction that has been born out of surveys, polls, and design workshops. They are almost never actual people with names and identities. Learning as much about your users is one of the most important jobs of any company, and it never stops. The polls, surveys, and design workshops certainly are valuable in that they begin the journey and can show many aspects of the customers, but there is so much more.

I’ve had numerous conversations that have started with my questions about customers and what they really know that quickly involve survey results where some percentage of those surveyed said some feature was important. I then ask if they’ve hit at least that same percentage in sales. It never does.

If you are going to try and build a software product using imaginary users, you should be happy with imaginary results.

Learn their names, what they like, what they don’t. Learn about them as people. Then their actions will cease to be mysterious.

-

Resource Management

“What is everyone working on?” Is probably the question I hate hearing the most. So many managers and leaders of companies focus their energy on optimizing their resources whether it be people, money, time, or scope that they can’t focus on why it mattered in the first place. Here’s a contrived example. An organization wants to increase revenue by 5% this quarter. This trickles down and transforms into a series of interesting objectives towards the bottom of the organization. Usually things like turning off servers (Cost reduction), or trying to build a set of features by a deadline (Time to market, and product management). So whips get cracked, people steel themselves to survive the time coming up, 40 hours a week turns into 50, then 60, then 80. Costs balloon and the deadline is missed, then moved, and maybe missed again.

If the reason why this happens remains elusive, let me connect the dots. Actually, let me do the opposite, let me disconnect the dots. If the goal was to increase revenue by 5%, that should have been the only dot. Worrying about everything else is a distraction. It also prevents everyone from having any chance of actually contributing to that problem.

Another way of putting is, if you have a team of 9 developers, 5 IT members, 2 designers, and you task them with shutting off servers for efficiency and cost reduction, and building features for a deadline, then the energy of those 16 people are put towards exactly that. Those 16 people aren’t going to increase revenue by 5%. They weren’t asked to.

Stop managing resources, and start managing results.

-

Chain of Command

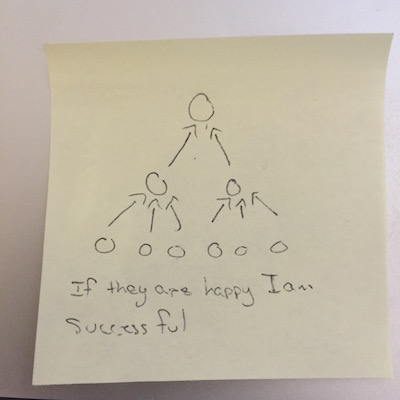

Along the same lines of what has previously been written, consider the basic structure of subordinates reporting to superiors. Almost all organizations are built in a basic pyramid that has this building block. Now, this isn’t awful. In fact, people crave structures like this all the time. However, what is wrong is how this structure winds up confusing people into failing.

There is a subtle thing in this relationship that I need to explain. I will be an exemplar employee, and promoted if I make those that I report to happy. This actually has very little to do with my performance, ability, or any of the other attributes that people claim to like.

Everyone has worked under someone that was awful and terrible, and while you can try to become good at internal politics, the situation is all too common that the way to succeed is just to satisfy that superior, no matter how absurd it is to do so.

Consider an alternative where your measure of success is related to the impact you have in accomplishing the goals of the organization, instead of what your superior says. This allows you the freedom to explore, to try, to fail, to discover, and to try a great deal more than whatever narrow task has been given. For managers this allows the people who report to you to actually help deliver on what you were always trying to without putting all of the risk on your shoulders to make the right choice on what should be done.